Introduction

In this chapter we will have the introduction, definition of statistics, collection and classification of data, formation of frequency distribution.(Goon and Dasgupta 1983) (Gupta and Kapoor 1997)

Origin of the word “Statistics”

Term statistics was derived from the Neo-Latin word

statisticum collegium meaning “council of state” and the Italian word

statista meaning “statesman” or “politician”.

A German word Statistik, got the meaning “collection and

classification of data” generally in the early 19th century. This word

was first introduced by Gottfried Achenwall (1749). Statistik was

originally designated as a term for analysis of data about the state

(data used by government or other administrative bodies). The term

Statistik was introduced into English in 1791 by Sir John Sinclair

when he published the first of 21 volumes titled “Statistical Account of

Scotland” (Ball 2004). The first book to have ‘Statistics’ in its title was

“Contributions to Vital Statistics” (1845) by Francis GP Neison,

actuary to the Medical Invalid and General Life Office.

Statistics and Mathematics

Mathematics follows a rigid theorem and proof. Mathematical theories

involve well-defined and proven facts which has the minimal scope of

change. However, Statistics is a discipline where real-life data is

handled. This factor makes this field of study more abstract, where

individuals have to develop newer solutions to problems that was new and

not observed before. Statistics is an applied science; in mathematics

the goal is to prove theorems. In statistics, the main goal is to

develop good methods for understanding data and making decisions.

Statisticians often use mathematical theorems to justify their methods,

but theorems are not the main focus. Statistics is now considered as an

independent field which uses mathematics to solve real life problems.

Definition of Statistics

Statistics is the science which deals with the

Two main branches of statistics are:

Descriptive statistics, which deals with summarizing data from a

sample using indexes such as the mean or standard deviation etc.

Inferential statistics, use a random sample of data taken from a

population to describe and make inferences about the population

parameters.

Data

Data can be defined as individual pieces of factual information recorded

and used for the purpose of analysis. It is the raw information from

which inferences are drawn using the science “STATISTICS”.

Example for data

No. of farmers in a village.

The rainfall over a period of time.

Area under paddy crop in a state.

Use and limitations of statistics

Functions of statistics: Statistics simplifies complexity, presents

facts in a definite form, helps in formulation of suitable policies,

facilitates comparison and helps in forecasting. Valid results and

conclusion are obtained in research experiments using proper statistical

tools.

Uses of statistics: Statistics has pervaded almost all spheres of

human activities. Statistics is useful in the administration, industry,

business, economics, research workers, banking,insurance companies etc.

Limitations of Statistics

Statistical theories can be applied only when there is variability

in the experimental material.

Statistics deals with only aggregates or groups and not with

individual objects.

Statistical results are not exact.

Statistics are often misused.

Population and Sample

Consider the following example. Suppose we wish to study the height of

all students in a college. It will take us a long time to measure the

height of all students of the college and so we may select 20 of the

students and measure their height (in cm). Suppose we obtain the

measurements like this

149 156 148 161 159 143 158 152 164 171 157 152 163 158 151 147 157 146

153 159

In this study, we are interested in the height of all students in the

college. The set of height of all students in the college is called the

population of this study. The set of 20 height, H = {149, 156,148,

…, 153, 159}, is a sample from this population.

Population

A population is the set of all objects we wish to study

Sample

A sample is part of the population we study to learn about the

population.

Variables and constants

Variables

Any type of observation which can take different values for different

people, or different values at different times, or places, is called a

variable. The following are examples of variables:

number of fruits in a branch, number of plots in a field, number of

schools in a country, etc.

plant height, yield, panicle length, temperature,etc.

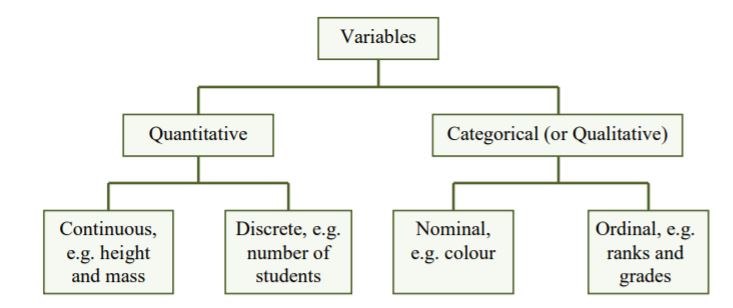

Broadly speaking, there are two types of variables – quantitative

and qualitative (or categorical) variables.

Constants

Constants are characteristics that have values that do not change.

Examples of constants are: pi (𝝅) = the ratio of the circumference of a

circle to its diameter (𝝅 = 3.14159...) and e, the base of the

natural or (Napierian) logarithms (e=2.71828).

Types of variables

Quantitative variables

A quantitative variable is one that can take numerical values. The

variables like number of fruits in a branch, number of plots in a field,

number of schools in a country, plant height, yield, panicle length,

temperature, etc. are examples of quantitative variables. Quantitative

variables may be characterized further as to whether they are discrete

or continuous

Discrete variables

The variables like number of fruits in a branch, number of plots in a

field, number of schools in a country, etc. can be counted. These are

examples of discrete variables. Variables that can only take on a finite

number of values are called “discrete variables.” Any variable phrased

as “the number of …”, is discrete, because it is possible to list its

possible values {0,1, …}. Any variable with a finite number of

possible values is discrete. The following example illustrates the

point. The number of daily admissions to a hospital is a discrete

variable since it can be represented by a whole number, such as 0, 1, 2

or 3. The number of daily admissions on a given day cannot be a number

such as 1.8, 3.96 or 5.33.

Continuous variables

The variables like plant height, yield, panicle length, temperature,

etc. can be measured. These are examples of continuous variables. A

continuous variable does not possess the gaps or interruptions

characteristic of a discrete variable. A continuous variable can assume

any value within a specific relevant interval of values assumed by the

variable. Notice that age is continuous since an individual does not age

in discrete jumps. Panicle length can be measured as 5.5, 5.8 cm etc so,

it is a continuous variable.

Categorical variables

A variable is called categorical when the measurement scale is a set of

categories. For example, marital status, with categories

(single,married, widowed), is categorical. Whether employed (yes, no),

religious affiliation (Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, others,

none), colours etc. Categorical variables are often called qualitative.

It can be seen that categorical variables can neither be measured nor

counted.

Measurement scales

Variables can further be classified according to the following four

levels of measurement: nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio.

Nominal scale

This scale of measure applies to qualitative variables only. On the

nominal scale, no order is required. For example,gender is nominal,

blood group is nominal, and marital status is also nominal. We cannot

perform arithmetic operations on data measured on the nominal scale.

Ordinal scale

This scale also applies to qualitative data. On the ordinal scale, order

is necessary. This means that one category is lower than the next one or

vice versa. For example, Grades are ordinal, as excellent is higher than

very good, which in turn is higher than good, and so on. It should be

noted that, in the ordinal scale, differences between category values

have no meaning.

Interval scale

This scale of measurement applies to quantitative data only. In this

scale, the zero point does not indicate a total absence of the quantity

being measured. An example of such a scale is temperature on the Celsius

or Fahrenheit scale. Suppose the minimum temperatures of 3 cities, A, B

and C, on a particular day were 00C, 200C and 100C, respectively.

It is clear that we can find the differences between these temperatures.

For example, city B is 200C hotter than city A. However, we cannot say

that city A has no temperature. Moreover, we cannot say that city B is

twice as hot as city C, just because city B is 200C and city C is

100C. The reason is that, in the interval scale, the ratio between two

numbers is not meaningful.

Ratio scale

This scale of measurement also applies to quantitative data only and has

all the properties of the interval scale. In addition to these

properties, the ratio scale has a meaningful zero starting point and a

meaningful ratio between 2 numbers. An example of variables measured on

the ratio scale, is weight. A weighing scale that reads 0 kg gives an

indication that there is absolutely no weight on it. So the zero

starting point is meaningful. If Ram weighs 60 kg and Laxman weighs 30

kg, then Ram weighs twice as Laxman. Another example of a variable

measured on the ratio scale is temperature measured on the Kelvin scale.

This has a true zero point.

Collection of Data

The first step in any enquiry (investigation) is the collection of data.

The data may be collected for the whole population or for a sample only.

It is mostly collected on a sample basis. Collecting data is very

difficult job. The enumerator or investigator is the well trained

individual who collects the statistical data. The respondents are the

persons from whom the information is collected.

Types of Data

There are two types (sources) for the collection of data:

- Primary Data

- Secondary Data

Primary Data

Primary data are the first hand information which is collected, compiled

and published by organizations for some purpose. They are the most

original data in character and have not undergone any sort of

statistical treatment.

Example: Population census reports are primary data because these are

collected, complied and published by the population census organization.

Secondary Data

The secondary data are the second hand information which is already

collected by an organization for some purpose and are available for the

present study. Secondary data are not pure in character and have

undergone some treatment at least once.

Example: An economic survey of England is secondary data because the

data are collected by more than one organization like the Bureau of

Statistics, Board of Revenue, banks, etc.

Methods of Collecting Primary Data

Primary data are collected using the following methods:

Personal Investigation

The researcher conducts the survey him/herself and collects data from

it. The data collected in this way are usually accurate and reliable.

This method of collecting data is only applicable in case of small

research projects.

Through Investigation

Trained investigators are employed to collect the data. These

investigators contact the individuals and fill in questionnaires after

asking for the required information. Most organizations utilize this

method.

Collection through Questionnaire

Researchers get the data from local representations or agents that are

based upon their own experience. This method is quick but gives only a

rough estimate.

Through the Telephone

Researchers get information from individuals through the telephone. This

method is quick and gives accurate information.

Methods of Collecting Secondary Data

Secondary data are collected by the following methods:

Official

Publications from the Statistical Division, Ministry of Finance, the

Federal Bureaus of Statistics, Ministries of Food, Agriculture,

Industry, Labor, etc.

Semi-Official

- Publications from State Bank, Railway Board, Central Cotton

Committee, Boards of Economic Enquiry etc.

- Publication of Trade Associations, Chambers of Commerce, etc.

- Technical and Trade Journals and Newspapers.

- Research Organizations such as universities and other institutions.

Difference Between Primary and Secondary Data

The difference between primary and secondary data is only a change of

hand. Primary data are the first hand information which is directly

collected form one source. They are the most original in character and

have not undergone any sort of statistical treatment, while secondary

data are obtained from other sources or agencies. They are not pure in

character and have undergone some treatment at least once.

Frequency distribution

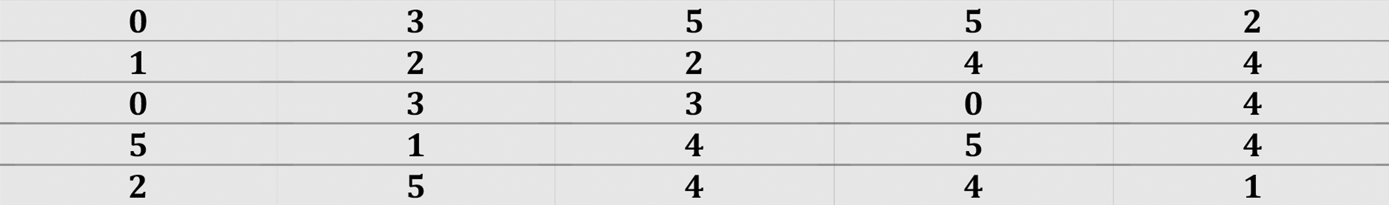

Table shows the number of fruits per branch in a mango

tree selected from a particular plot. The data, presented in this form

in which it was collected, is called raw data.

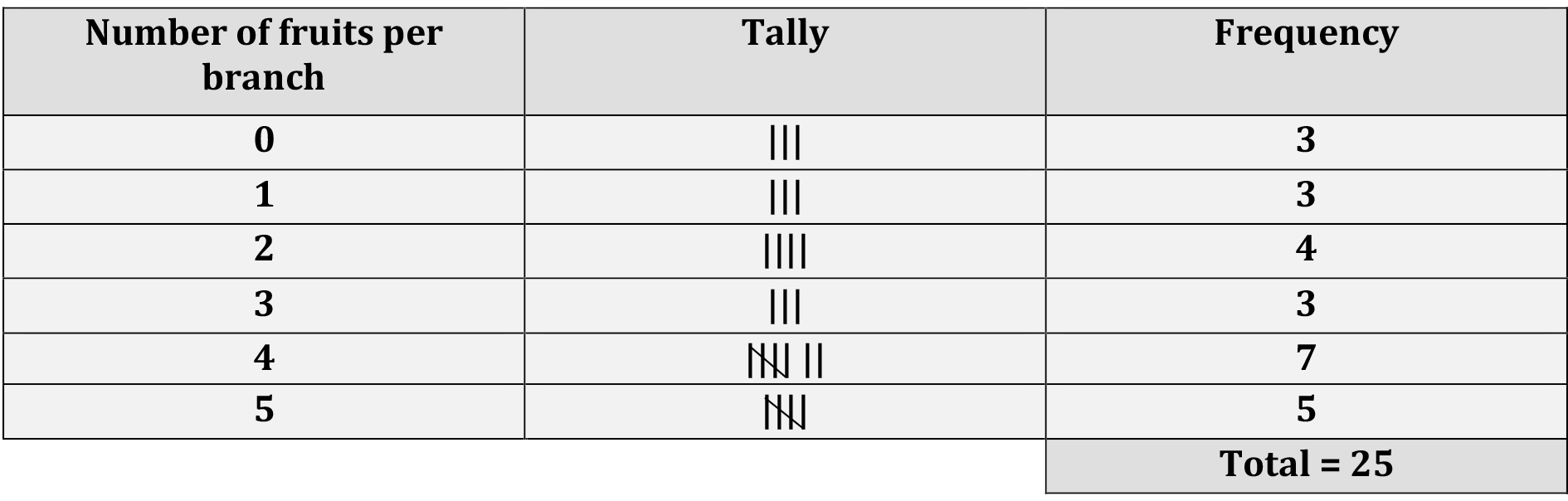

It can be seen that, the minimum and the maximum numbers of fruits per branch are 0 and 5, respectively. Apart from these numbers, it is impossible, without further careful study, to extract any exact information from the data. But by breaking down the data into the form below

Now certain features of the data become apparent. For instance, it can easily be seen that, most of the branches selected have four fruits because number of branches having 4 fruits is 7. This information cannot easily be obtained from the raw data. The above table is called a frequency table or a frequency distribution. It is so called because it gives the frequency or number of times each observation occurs. Thus, by

finding the frequency of each observation, a more intelligible picture is obtained.

Construction of frequency distribution

List all values of the variable in ascending order of magnitude.

Form a tally column, that is, for each value in the data, record a

stroke in the tally column next to that value. In the tally, each

fifth stroke is made across the first four. This makes it easy to

count the entries and enter the frequency of each observation.

Check that the frequencies sum to the total number of observations

Grouped frequency distribution

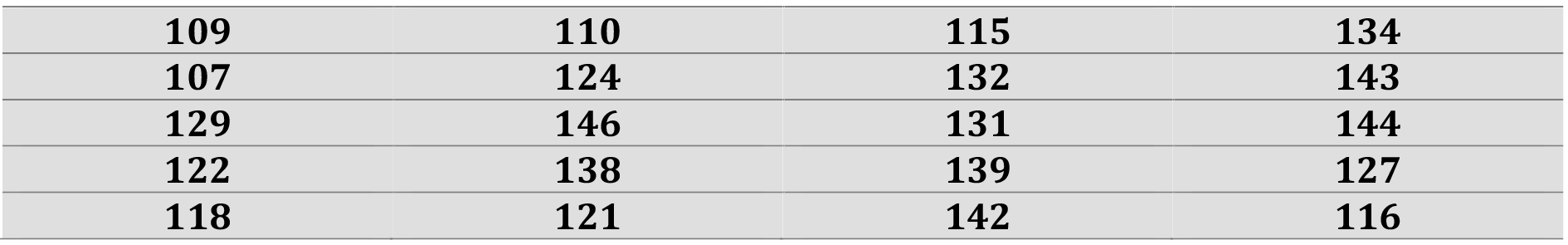

Data below gives the plant height of 20 paddy varieties, measured to the

nearest centimeters.

It can be seen that the minimum and the maximum plant height are 107 cm

and 144 cm, respectively. A frequency distribution giving every plant height between 107 cm and 144 cm would be very long and would not be very

informative. The problem is to overcome by grouping the data into

classes.

If we choose the classes

100 – 109

110 – 119

120 – 129

130 – 139

140 – 149

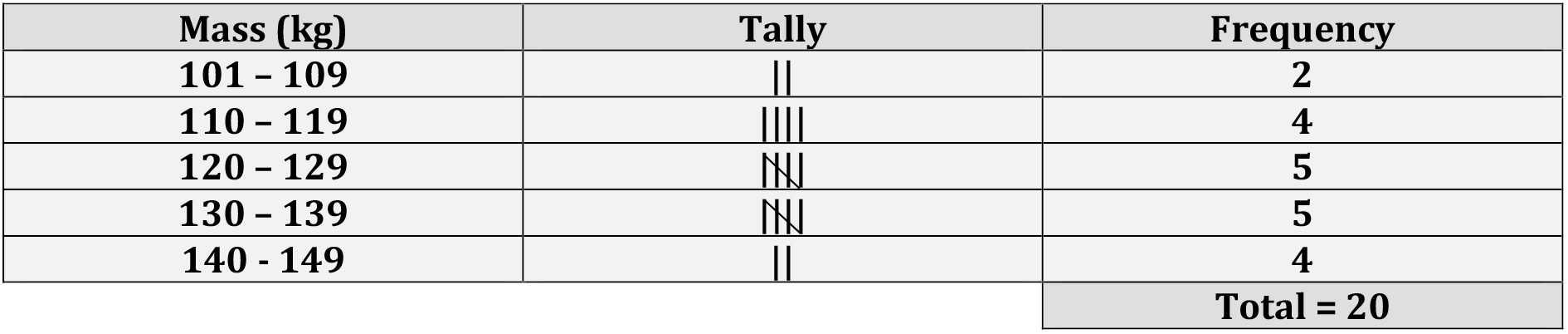

we obtain the frequency distribution given below:

Above table gives the frequency of each group or class; it is therefore

called a grouped frequency table or a grouped frequency distribution.

Using this grouped frequency distribution, it is easier to obtain

information about the data than using the raw data. For instance, it can

be seen that 14 of the 20 paddy varieties have plant height between 110

cm and 139 cm (both inclusive). This information cannot easily be

obtained from the raw data.

It should be noted that, even though above table is concise, some

information is lost. For example, the grouped frequency distribution

does not give us the exact plant height of the paddy varieties. Thus the

individual plant height of the paddy varieties are lost in our effort to

obtain an overall picture.

Terms used in grouped frequency tables.

Class limits

The intervals into which the observations are put are called class

intervals. The end points of the class intervals are called

class limits. For example, the class interval 100 – 109,

has lower class limit 100 and upper class limit 109.

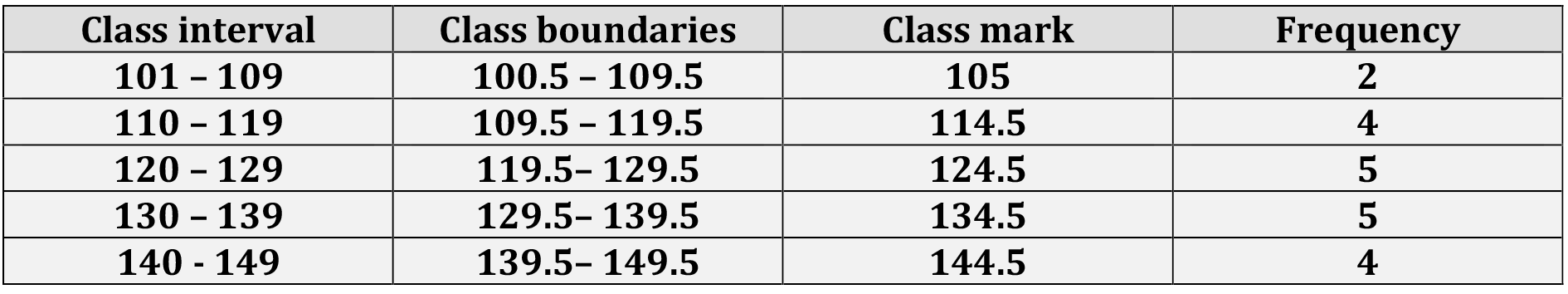

Class boundaries

The raw data in the above example were recorded to the nearest

centimeters. Thus, a plant height of 109.5cm would have been recorded as

110cm, a plant height of 119.4 cm would have been recorded as 119cm,

while a plant height of 119.5 cm would have been recorded as 120 cm. It

can therefore be seen that, the class interval 110 – 119, consists of

measurements greater than or equal to 109.5 cm and less than 119.5 cm.

The numbers 109.5 and 119.5 are called the lower and upper boundaries of

the class interval 110 – 120. The class boundaries of the other class

intervals are given below:

Note:

Notice that the lower class boundary of the ith class interval is the

mean of the lower class limit of the class interval and the upper class

limit of the (i-1)th class interval (i = 2, 3, 4, …). For example,

in the table above the lower class boundaries of the second and the

fourth class intervals are (110 + 119) /2 = 114.5 and (130 + 139)/2 =

134.5 respectively.

It can also be seen that the upper class boundary of the ith class

interval is the mean of the upper class limit of the class interval and

the lower class limit of the (i+1)th class interval (i = 1, 2, 3,

…). Thus, in the above table the upper class boundary of the fourth

class interval is (130 + 139)/2 = 134.5.

Class mark

The mid-point of a class interval is called the class mark or class

mid-point of the class interval. It is the average of the upper and

lower class limits of the class interval. It is also the average of the

upper and lower class boundaries of the class interval. For example, in

the table, the class mark of the third class interval was found as

follows: class mark =(120+129)/2 = (119.5 + 129.5)/2= 124.5.

Class width

The difference between the upper and lower class boundaries of a class

interval is called the class width of the class interval. Class widths

of class intervals can also be found by subtracting two consecutive

lower class limits, or by subtracting two consecutive upper class

limits.

Note:

The width of the ith class interval is the numerical difference

between the upper class limits of the ith and the ( i-1)th class

intervals (i = 2, 3, …). It is also the numerical difference between

the lower class limits of the ith and the (i+1)th class intervals (i

= 1, 2, …).

In grouped frequency table above the width of the second class interval

is |110-119| = 9. This is the numerical difference between the lower

class limits of the second and the third class intervals. The width of

the third class interval is |120-129|= 9. This is the numerical

difference between the lower class limits of the third and the fourth class intervals.

Construction of frequency distribution table

Step 1. Decide how many classes you wish to use.

Step 2. Determine the class width

Step 3. Set up the individual class limits

Step 4. Tally the items into the classes

Step 5. Count the number of items in each class

Consider the example

An agricultural student measured the lengths of leaves on an oak tree

(to the nearest cm). Measurements on 38 leaves are as follows

9,16,13,7,8,4,18,10,17,18,9,12,5,9,9,16,1,8,17,1,10,5,9,11,15,6,14,9,1,12,5,16,4,16,8,15,14,17

Step 1. Decide how many classes you wish to use.

H.A. Sturges provides a formula for determining the approximation number

of classes. \[\mathbf{k = 1 + 3.322}\mathbf{\log}\mathbf{N}\] Number of

classes should be greater than calculated k

In our example N=38, so k= (1+3.322)×log(38) = (1+3.322)×1.5797 =

6.24 = approx 7

So the approximated number of classes should be not less than 6.24

i.e.\(\ k^{'}\) =7

Step 2. Determine the class width

Generally, the class width should be the same size for all classes. C=

| max − min|/ k. Class width \(C^{'}\)should be greater than calculated

C. For this example, C = | 18− 1|/6.24 = 2.72, so

approximately class width \(C^{'} =\) 3 (Note that k used here is the

calculated value using Sturges formula not the approximated).

Step 3. To set up the individual class limits, we need to find the

lower limit only

\[L = min - \frac{C^{'} \times k^{'} - (max - min)}{2}\]

where C and k here are final approximated class width and number of

classes respectively in our example

\(L = 1 - \frac{(3 \times 7) - (18 - 1)}{2}\)=1-2=-1; since there is no

negative values in data = 0.

|

Class

|

Frequency

|

|

0-3

|

3

|

|

3-6

|

5

|

|

6-9

|

5

|

|

9-12

|

9

|

|

12-15

|

5

|

|

15-18

|

9

|

|

18-21

|

2

|

Even though the student only measured in whole numbers, the data is

continuous, so “4 cm” means the actual value could have been anywhere

from 3.5 cm to 4.5 cm.

Cumulative frequency

In many situations, we are not interested in the number of observations

in a given class interval, but in the number of observations which are

less than (or greater than) a specified value. For example, in the above

table, it can be seen that 3 leaves have length less than 3.5 cm and 9

leaves (i.e. 3 + 6) have length less than 6.5 cm. These frequencies are

called cumulative frequencies. A table of such cumulative frequencies is

called a cumulative frequency table or cumulative frequency

distribution.

Cumulative frequency is defined as a running total of frequencies.

Cumulative frequency can also defined as the sum of all previous

frequencies up to the current point. Notice that the last cumulative

frequency is equal to the sum of all the frequencies. Two types of

cumulative frequencies are Less than cumulative frequency and Greater

than cumulative frequency. Less than cumulative frequency (LCF) is the

number of values less than a specified value. Greater than cumulative

frequency (GCF) is the number of observations greater than a specified

value.

The specified value for LCF in the case of grouped frequency

distribution will be upper limits and for GCF will be the lower limits

of the classes. LCF’s are obtained by adding frequencies in the

successive classes and GCF are obtained by subtracting the successive

class frequencies from the total frequency.

Relative frequency

It is sometimes useful to know the proportion, rather than the number,

of values falling within a particular class interval. We obtain this

information by dividing the frequency of the particular class interval

by the total number of observations. Relative frequency of a class

is the frequency of class divided by total observations. Relative

frequencies all add up to 1.

|

Class

|

Frequency

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

|

0.5 - 3.5

|

3

|

3

|

38

|

0.078947

|

|

3.5 - 6.5

|

6

|

9

|

35

|

0.157895

|

|

6.5 - 9.5

|

10

|

19

|

29

|

0.263158

|

|

9.5 - 12.5

|

5

|

24

|

19

|

0.131579

|

|

12.5 - 15.5

|

5

|

29

|

14

|

0.131579

|

|

15.5 - 18.5

|

9

|

38

|

9

|

0.236842

|

[1] “Note: A= Less than cumulative frequency; B= Greater than cumulative frequency, C = Relative frequency”

“Data is the sword of the 21st century, those who wield it

well, the Samurai.” - Jonathan Rosenberg, former Google SVP