9 Probability

Many events can’t be predicted with total certainty. The best we can say is how likely they are to happen, using the idea of probability.

9.1 Tossing a Coin

When a coin is tossed, there are two possible outcomes:

heads (H) or

tails (T)

We say that the probability of the coin landing H is ½ and the probability of the coin landing T is ½

9.2 Throwing Dice

When a single die is thrown, there are six possible outcomes: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. The probability of getting any one of them is \(\frac{1}{6}\)

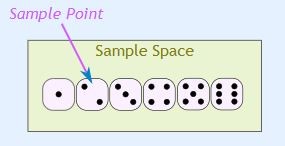

Figure 9.1: Image of dice (plural)

9.3 Playing cards

A standard deck of playing cards consists of 52 cards divided into 4 suits (Spades, Hearts, Diamonds, Clubs) of 13 cards each

Figure 9.2: Image of a spade symbol

Spades : - 13 cards, which include 9 numbered cards from 2 to 10 and picture cards Ace, King, Queen, Jack

Figure 9.3: Image of a hearts symbol

Hearts : - 13 cards

Figure 9.4: Image of a diamond symbol

Diamonds :- 13 cards

Figure 9.5: Image of a clubs symbol

Clubs :- 13 cards

Red cards:- 26 cards and Black cards:- 26 cards

9.4 Probability

In general:

Probability of an event happening = \(\frac{\text{Number of ways it can happen}}{\text{Total number of outcomes}}\)

Example 1

The chances of rolling a "4" with a die

Number of ways it can happen: 1 (there is only 1 face with a "4" on it)

Total number of outcomes: 6 (there are 6 faces altogether)

So the probability = \(\frac{1}{6}\)

Example 2

There are 5 marbles in a bag: 4 are blue, and 1 is red. What is the probability that a blue marble gets picked?

Number of ways it can happen: 4 (there are 4 blues)

Total number of outcomes: 5 (there are 5 marbles in total)

So the probability = \(\frac{4}{5}\) = 0.8

Must learn definitions

Random experiment: A random experiment is an experiment or a process for which the outcome cannot be predicted with certainty.

Eg: Tossing a coin; Tossing a coin five times; Choosing a card from deck of cards; Tossing a die.

Sample space: The sample space (denoted S) of a random experiment is the set of all possible outcomes.

Eg: Throwing a coin generates the sample space; S={H,T},Throwing a die: S= {1,2,3,4,5,6}

Sample point: Just one of the possible outcomes. Eg: heads, the 5 of Clubs in cards. There are 6 different sample points in the sample space of throwing a die.

Exercise1: Check yourself

If a die is tossed

- What is the sample space?

- What is the probability of getting a 1?

- What is the probability of obtaining a even number?

- What is the probability of getting a 7?

Answers given in section 9.9

Figure 9.6: Sample space in throwing a die

9.4.1 Event

One or more outcomes of a random experiment

An event can be just one outcome:

Getting a Tail when tossing a coin

Rolling a "5"

An event can include more than one outcome:

Choosing a "King" from a deck of cards (any of the 4 Kings)

Rolling an "even number" (2, 4 or 6)

Example

Ram wants to see how many times a "double" (both dice have same number) comes up when throwing 2 dice.

The Sample Space is all possible Outcomes (36 Sample Points):

{1,1} {1,2} {1,3} {1,4} ... {6,3} {6,4} {6,5} {6,6}

The Event Ram is looking for is a "double", where both dice have the same number. It is made up of these 6 Sample Points:

{1,1} {2,2} {3,3} {4,4} {5,5} and {6,6}

9.4.1.1 Types of Events

Independent Events

Events can be "Independent", meaning each event is not affected by any other events.

Eg: You toss a coin and it comes up "Heads" three times. what is the chance that the next toss will also be a "Head"?

The chance is simply ½ (or 0.5) just like any other toss of the coin. Past will not affect the current toss.

Dependent Events

But some events can be "dependent", which means they can be affected by previous events. after taking one card from the deck there are less cards available, so the probabilities change!

Let's look at the chances of getting a King from a deck of cards

For the 1st card the chance of drawing a King is 4 out of 52

But for the 2nd card:

If the 1st card was a King, then the 2nd card is less likely to be a King, as only 3 of the 51 cards left are Kings.

If the 1st card was not a King, then the 2nd card is slightly more likely to be a King, as 4 of the 51 cards left are King.

Note

Replacement: When we put each card back after drawing it the chances don't change, as the events are independent.

Without Replacement: The chances will change, and the events are dependent.

Mutually Exclusive Events

Mutually Exclusive means we can't get both events at the same time. It is either one or the other, but not both

Examples:

Turning left or right are Mutually Exclusive (you can't do both at the same time)

Heads and Tails are Mutually Exclusive

Kings and Aces are Mutually Exclusive

What isn't Mutually Exclusive?

Kings and Hearts are not Mutually Exclusive, because we can have a King of Hearts!

Exhaustive Events

A set of events is called exhaustive if all the events together make the entire sample space.

For example,

Sample space of tossing a die is \(S\)= {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

Then the

Event A: getting an even number; {2, 4, 6}

Event B: getting an odd number; {1, 3, 5}

are exhaustive events because together they makes the entire sample space.

Equally likely events

Equally likely events are events that have the same theoretical probability of occurring.

For example: Tossing a coin

Event A: getting a head

Event B: getting a tail

Both events have equal probability of occurring; these events are so termed as equally likely events

9.5 Definition of Probability

9.5.1 Mathematical Definition

If an experiment with \(n\) exhaustive, mutually exclusive and equally likely outcomes, \(m\) outcomes are favourable to the happening of an event \(E\), the probability \(p\) of happening of E is given by

\[P\left( E \right) = p = \ \frac{m}{n}\]

\(p\) is termed as probability of success.

Example

When a coin is tossed, there are two possible outcomes Heads or Tails. Outcomes are exhaustive, mutually exclusive and equally likely.

Consider the event \(E\) : getting a head

Probability of event \(E\), \(p(E)\) is denoted as \(p\)

\(p\) is given by the definition as:

\(m\) = number of outcomes are favourable to the happening of event \(E\) = 1

\(n\) = number of outcomes (Head and Tail) = 2

\[P\left( E \right) = p = \ \frac{m}{n}\]

\[P\left( E \right) = p = \ \frac{1}{2}\]

i.e. probability of getting a Head is ½

Above definition have following limitations

What will happen if the outcomes are not equally likely. For example in tossing of a biased die.

Probability cannot be defined if the total cases ‘n’ is unknown or tends to infinity. For example; what is the probability of raining tomorrow?

To overcome these limitations, other definitions are given

9.5.2 Statistical Definition

The probability 'p' of happening of E is given by

\[P\left( E \right) = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty}\frac{m}{n}\]

where \(n\) is the number of times the process (e.g., tossing the die) is performed which tends to infinity, and \(m\) is the number of times the outcome ‘\(E\)’ happens.

Above definition also has some limitations

In some cases, the experiment could never in practice be carried out more than once.

It leaves open the question of how large \(n\) has to be before we get a good approximation.

To overcome these limitations, another approach to probability was introduced by Russian mathematician A.N. Kolmogorov. In this approach no precise definition is given, instead certain axioms or postulates on which probability calculations are based.

9.5.3 Axiomatic Approach

Whole field of probability theory is based on the following three axioms

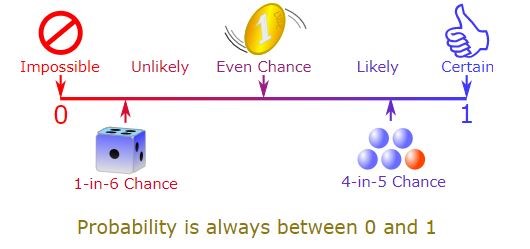

Probability of an event, P (\(E\)) lies between 0 and 1.That is \(0 \leq P(E) \leq 1\)

Probability of entire sample space is 1. That is \(P\left( S \right) = 1\)

If A and B are mutually exclusive events then probability of occurrence of either A or B denoted by \(P(A \cup B)\) shall be given by \(P\left( A \cup B \right) = P\left( A \right) + P(B)\)

Some interesting facts on probability

Probability \(p\) of the happening of an event is known as the probability of success and the probability \(q\) of the non-happening of the event as the probability of failure.

\(p\) as well as \(q\) are non-negative and cannot exceed unity. i.e., 0 ≤ \(p\) ≤ 1 and 0 ≤ \(q\) ≤ 1. Thus, the probability of occurrence of an event lies between 0 and 1 [including 0 and 1].

Probability of an impossible event is 0 and that of a sure event is 1. If \(p(A)\) = 1, the event A is certainly going to happen and if \(p(A)\) = 0, the event is certainly not going to happen.

The number (\(m\)) of favorable outcomes to an event cannot be greater than the total number of outcomes (\(n\)).

Figure 9.7: Sample space in throwing a die

Additional Problems

- In a simultaneous toss of two coins, find the probability of (i) getting 2 heads. (ii) exactly 1 head?

Solution

Here, the possible outcomes are HH, HT, TH, TT. i.e., Total number of possible outcomes = 4.

\(i)\) Number of outcomes favorable to the event (2 heads) = 1 (i.e.,HH).

\(p\)(2 heads) = 1/4 .

\(ii)\) Now the event consisting of exactly one head has two favourable cases, namely HT and TH

\(p\)(exactly one head) = 2 /4 = 1/ 2

- In a single throw of two dice, what is the probability that the sum is 9?

Solution

The number of possible outcomes is 6 × 6 = 36.

(1,1) (1,2) (1,3) (1,4) (1,5) (1,6)

(2,1) (2,2) (2,3) (2,4) (2,5) (2,6)

(3,1) (3,2) (3,3) (3,4) (3,5) (3,6)

(4,1) (4,2) (4,3) (4,4) (4,5) (4,6)

(5,1) (5,2) (5,3) (5,4) (5,5) (5,6)

(6,1) (6,2) (6,3) (6,4) (6,5) (6,6)

Event A: sum is 9

four outcomes are there with sum 9, they are (5,4), (6,3), (3,6), (4,5)

Probability (sum is 9) = 4/36= 1/9

- From a bag containing 10 red, 4 blue and 6 black balls, a ball is drawn at random. What is the probability of drawing (i) a red ball? (ii) a blue ball? (iii) not a black ball?

There are 20 balls in all. So, the total number of possible outcomes is 20

\(i)\) Number of red balls = 10

\(p\)(getting a red ball ) = 10/20 = 1/2

\(ii)\) Number of blue balls = 4

\(p\)(getting a blue ball ) = 4/20 = 1/5

\(iii)\) Number of balls which are not black = 14

\(p\)(not a black ball ) = 14/20 = 7/10

9.6 Event relations

Consider tossing of a die. If A be the event of getting an even number, then the sample points 2, 4 and 6 are favorable to the event A. The remaining sample points 1, 3 and 5 are not favorable to the event A. Therefore, these will occur when the event A will not occur. In an experiment, the outcomes which are not favorable to the event A are called complement of A and are denoted by 'not' A or by Ac

9.6.1 Event A or B

Denoted as (A \(\cup\) B), spelled as A union B

Let us consider the example of throwing a die. A is an event of getting a multiple of 2 and B be another event of getting a multiple of 3. The outcomes 2, 4 and 6 are favourable to the event A and the outcomes 3 and 6 are favourable to the event B.

i.e.

A= {2, 4, 6}

B= {3, 6}

Then A ꓴ B = { 2, 3, 4,6}

Again, if A be the event of getting an even number and B is another event of getting an odd number, then

A = { 2, 4, 6 }

B = { 1, 3, 5 }

Then A ꓴ B = {1, 2, 3, 4,5,6}

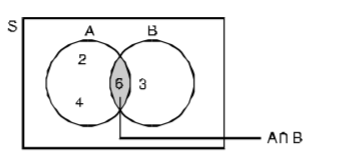

9.6.2 Event A and B

Denoted as (A ꓵ B) spelled as A intersection B. On throwing a die in which A is the event of getting a multiple of 2 and B is the event of getting a multiple of 3. The outcomes favorable to A are 2, 4, 6 and the outcomes favorable to B are 3, 6. Here 6 is present in both A and B so here A ꓵ B = 6

Figure 9.8: Venn diagram showing intersection

9.7 Additive law of Probability

For any two events A and B of a sample space S,

\(p\)(AꓴB) = \(p\)(A)+\(p\)(B) − \(p\)(AꓵB)

For mutually exclusive case \(p\)(AꓵB)=0; in that case \(p\)(AꓴB )= \(p\)(A )+\(p\)(B ).

Example

- A card is drawn from a well-shuffled deck of 52 cards. What is the probability that it is either a spade or a king?

If A denotes the event of drawing a 'spade card'. B denotes the events of drawing a 'king' respectively. The event A consists of 13 sample points, whereas the event B consists of 4 sample points.

\(p\)(A)= 13/52

\(p\)(B)= 4/52

\(p\)( AꓵB) = 1/52

\(p\)(AꓴB)= \(p\)(A)+\(p\)(B) − \(p\)(AꓵB) = 13/52+4/52-1/52 = 4/13

- In a single throw of two dice, find the probability of a total of 9 or 11.

Let the events A= a total of 9 and B= a total of 11.

Events are mutually exclusive A ꓵ B = 0

Now \(p\)(A) = \(p [(3, 6), (4, 5), (5, 4), (6, 3)] = 4 /36\)

\(p\)(B) = \(p[(5, 6), (6, 5)] = 2 /36\)

Thus, \(p(AꓴB) = 4/36 +2/36 = 6/36 = 1/6\)

9.8 Multiplication law of probability

If A and B are independent events, then

\(p\)(AꓵB) = \(p\)(A). \(p\)(B)

It is called as the Multiplication law of probability

- A die is tossed twice. Find the probability of a number greater than 4 on each throw.

Let us denote by A, the event 'a number greater than 4' on first throw. B be the event 'a number greater than 4' in the second throw. Clearly A and B are independent events. In the first throw, there are two outcomes, namely, 5 and 6 favourable to the event A.

∴ \(p\)(A) =2/6 = 1/3

Similarly in the second throw, there are two outcomes, namely, 5 and 6 favourable to the event A.

∴ \(p\)(B) = 2/6 = 1/3

Hence, \(p\)(A and B) = \(p\)(AꓵB) = \(p\)(A).\(p\)(B) = 1 /3 ×1 /3 = 1/9

Probability using combinations

Knowledge of combinations can be applied to find total number of possible outcomes.

nCr\(= \frac{n!}{r!(n - r)!}\)

For example 3C2\(= \frac{3!}{2!(3 - 2)!} = \frac{3 \times 2 \times 1}{2 \times 1(1)} = 3\)

Now let us see with example how this is used in probability

A bag contains 3 red, 6 white and 7 blue balls. What is the probability that two balls drawn are white and blue?

Total number of balls = 3 + 6 + 7 = 16

Out of 16 balls, 2 balls can be drawn in 16C2 ways

i.e. 16C2 = 120.

Out of 6 white balls, 1 ball can be drawn in 6C1 ways and out of 7 blue balls, one can be drawn is 7C1 ways. Since each of the former case is associated with each of the later case, therefore total number of favorable cases is 6C1 × 7C1

Therefore required probability= (6C1 × 7C1) / 16C2 = 42/120 = 7/20

Find the probability of getting both red balls, when from a bag containing 5 red and 4 black balls, two balls are drawn

Total number of balls = 9

Out of 9 balls, 2 balls can be drawn in 9C2 ways

No of ways both are red balls can be taken = 5C2

Hence \(p\)(both red balls ) = 5C2 / 9C2 = 5/18

Six cards are drawn at random from a pack of 52 cards. What is the probability that 3 will be red and 3 black?